Contributions towards a global online event themed on 'multilingual digital humanities'

DayofDH2021 logo

By Pete Chonka and Cristina Moreno Almeida with introduction by Paul Spence

This year’s Day of Digital Humanities event Day of DH 2021 presents another opportunity to engage with the wider digital humanities community through a series of interactions channelled through Twitter and Instagram with the hashtag #dayofdh2021. The focus this year is on ‘multilingual DH’, a topic which has been at the centre of my research in the last four or five years, and which has thankfully started to gain traction in recent years through initiatives such as the multilingual Open Methods initiative, multi-language versions of the Programming Historian and multilingual DH. As Quinn Dombrowski remarked recently, "Multilingual DH is suddenly blooming".

I asked colleagues from the Department of Digital Humanities at King’s College London to describe research they are doing on multilingual digital studies. What follows are a few examples of their work.

Image by Pete Chonka

Far keliya fool ma dhaqdo – one finger cannot wash a face

Or: the problems of mono-lingualism in digital culture studies

Pete Chonka

As a researcher interested in the social, cultural and political impacts of digital media technologies in East Africa, I’m always thinking about the importance of indigenous languages in the dynamic online spaces I study. I often focus on the Somali-speaking parts of this region, and this is a language that I’ve studied and worked with for more than a decade. I’d never describe myself as being fluent – the poetic form of Somali is so rich that I’m still way off full competence there – but I read and speak the language well enough to use it in different aspects of my research.

It’s clear that our field – digital humanities – has a problem with Anglophone monolingualism: the global dominance of the English language. Of course, this is also an issue for Western academia more generally, but because so much ‘cutting edge’ research on digital cultures and societies often focuses on North American or European contexts this compounds the problem. As many scholars have shown, we need to decolonise our approaches and stop universalising Western dynamics and experiences of digital culture as though they automatically reflect people’s engagements with technology worldwide. I believe that thinking carefully about how a world of different languages are used on digital platforms – and how they interact with the ‘algorithmic power’ that so many of us are concerned with – can help with this. As the Somali proverb in the title says, one finger cannot wash a face. I’d argue that this is the same for languages and our understanding of (global) digital cultures - pervasive mono-lingualism can be a huge limiting factor in our studies.

I’ve considered some of these questions in relation to the Datafication and Digital Rights in East Africa network project that I have been involved in over the last year. Our UKRI-funded network has brought together scholars, tech practitioners and civil society activists in and beyond the region to think critically about how digital platforms (and the value of data in East African digital economies, communication practices and humanitarian settings) are influencing societies in that part of the world. Along with colleagues, I’ve been experimenting and thinking through how the vast amounts of data that are generated on online platforms by East African-language users are harvested by these tech companies. To what extent do the algorithms that gather data to target personalised advertising or predict search results ‘get’ the content that is being generated by users writing in a language like Somali? We have to remember that this is a context where the Somali-language is only partially machine translatable – put simply, Google translate for Somali just isn’t very good! What do these linguistic differences mean for the ‘power’ of algorithms to affect how people come across, access and share information on ‘global’ platforms, but in ‘local’ languages? In the work we have done so far on search auto-complete functions in languages like Somalia, Amharic and Swahili, we argue that this is an area that needs much more attention.

The importance of multi-lingualism here is not just about the research itself, but also about how we communicate our findings with wider audiences. Again, the dominance of English in academic publishing is hardly news - though it is certainly a problem. We also have to recognise the continued centrality of English as a regional lingua-franca amongst the kind of researcher, civil society and tech practitioner communities who we work with across different East African countries in our network. Nevertheless, I’ve always tried to make an effort to use my (modest) Somali language skills to share findings from different research projects directly with those affected by the things I study and to reach audiences who don’t necessarily speak English. For example, we have started to complement the English-language blogs produced by and with our network partners with podcasts in languages such as Somali. These are designed to give an opportunity for our contributors to discuss in East African languages the findings they’ve highlighted in their written outputs. We’re still in the early stages of this, but my own experiences (along with insight from our partners) indicate that for many people in the region who do not speak English an audio podcast conversation may be more engaging than a written translation of the work into Somali. That’s not to say that promoting written Somali as an academic language is not important – it is! And so many cultural activists are promoting Somali publishing in the region – but using a variety of formats in multiple languages tailored to different audiences can be beneficial.

Our Datafication and Digital Rights in East Africa project has been affected by UK Government cuts to Official Development Assistance research funding and some of our bigger plans for the future of the network will need to change (that’s another story, and for more on the extremely damaging and disruptive impact of these cuts on global research partnerships see here). Nonetheless, we will continue to experiment with multilingual research ‘outputs’ and learn from our colleagues in the region who communicate with diverse multilingual audiences on a daily basis. We shouldn’t forget that multi-lingualism is the norm rather than the exception in East Africa. It’s a sign of my white privilege that people sometimes marvel at me speaking Somali. In those instances, I always try to emphasise the fact that my language skills pale (as it were) in comparison with so many people in the region itself, for whom multilingualism (in Amharic, Arabic, Af Maxaa Tiri Somali, Af Maay Somali, Kikuyu, Kamba, Oromo, Sheng, Swahili… the list goes on) is just part of daily life. Western academia needs to catch up and think more seriously about how multilingualism affects digital cultures in different ways around the world.

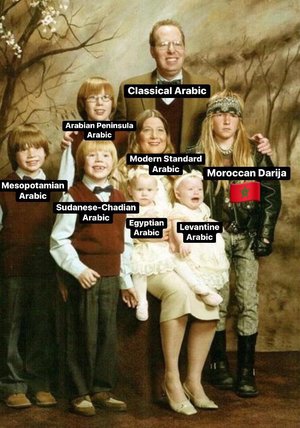

Popular facebook meme

Digital Languages: The Case of Darija

Cristina Moreno Almeida

My line of research at DDH is focused on popular digital culture in North Africa, more precisely Morocco. I look at multimodal online cultural production such as memes, animated cartoons or music videos which normally employ a language quite distinct from Arabic, the country’s official language. The online cultural production I analyse is mostly in Darija, a language most Moroccans use in their everyday lives. Darija is frankly quite difficult to define with a few words. Without falling down the rabbit hole of Moroccan sociolinguistics, Darija can be described as having common grounds with Modern Standard Arabic, but with important grammatical differences including words derived from Tamazigh (Berber), French, Spanish and more recently English. There are local variants, some of which are associated with social class, complicating the matter even more. Although Darija has sometimes been described as an oral language, one can find texts written in Darija. However, it is in the era of social media where Darija has reclaimed its central status as the ruling language of the Moroccan internet. Darija is dominant on Facebook comment sections, YouTube videos, Instagram Stories and TikTok. It is precisely the penetration of internet and ICTs from text messages to social media that has propelled such an amount of oral and written text in a language that is still not official in Morocco. Initially, many of these texts in Darija, and for that matter all the other local languages written by users within the Arabic speaking world, employed an alphanumeric Latinized Arabic because of technological deficiencies for non-Latin characters. Advances in technology have made exchanging languages and alphabets on our digital keyboards easier leading to a wider use of the Arabic characters. An added complication in the use of two different sets of characters is that as a non-official language Darija lacks a normalised grammar. Therefore, words may be spelled differently, complicating any research in this language, for example affecting searches on relevant words or hashtags on Twitter. A further complication in researching online cultures in Darija are the use of neologisms especially concerning young people’s language use. While there are a few bilingual dictionaries of Moroccan Darija into English, French and Spanish, these have not been able to keep up with contemporary youth. Automated translations and transcriptions are useless as they cannot decipher this language. During my work on Moroccan rap, I termed this variant Street Darija or Darija dyal zan9a in contrast with other more enhanced and literary forms of Darija used in formal situations, magazines, poetry and other literary genres. This variant of Darija is mostly differentiated, although not uniquely, by the use of slurs and perceived as popular, as well as more virile and tough. Because Street Darija denotes a certain authenticity in reflecting the real talk, it bestows credibility to those who use it in their expressive cultures. This is the case with comics, rap music, movies, or animated cartoons which dare to jump the hurdles of what is deemed to be socially acceptable in public spheres. Online, Street Darija is employed profusely on discussions taking place on social media especially within groups mainly inhabited by young people. Research in this area is of great significance precisely because this language and its more youthful variant remain unofficial. My research at DDH seeks therefore, at its core, to shed light into the ways in which an unofficial language like Darija, and Street Darija as its most loyal variant to everyday youthful life, has evolved side by side with social and digital, media morfing into different forms and resisting attempts to be cornered as an unimportant language in the so-called age of the anglophone.