Guest blog by Maria Grazia Sindoni

In this guest blog, Maria Grazia Sindoni of the University of Messina, Italy, looks at frameworks for critical digital literacy in modern languages, and asks if standardisation is necessarily a good thing.

A couple of months ago, I was asked – and not for the first time – by a student about the difference between multimodality and multimedia and I found myself giving examples that contrasted sign-making and technology over time and across cultures. We are now surrounded by an unprecedented interplay of semiotic resources, or modes, such as language(s), images, music, etc., that are orchestrated together to make meanings by sign-makers in different contexts and cultures. In my view, no text is monomodal, that is, no communicative event makes use of only one resource at a time to produce meanings, and here I embrace the view expressed by Anthony Baldry and Paul Thibault in their 2006 ground-breaking volume. It would be misleading indeed to think that multimodality is a consequence of digitality or of the development of multimedia technologies, as the examples of Middle Age illuminated manuscripts or even prehistoric cave paintings show. However, it is nonetheless true that digitality has made the communicative arena more complex than ever. Multimodal approaches to communication foreground socio-semiotic meaning-making and, as such, are profoundly different from studies that focus on multimedia in its technical affordances. It is the difference between what you can mean and what you can do with tools and languages.

Seen from this angle, language is considered as one resource among others, and not as necessarily the most important one, so that the first challenge for teachers that grapple with foreign languages and digital literacies at any level is how to raise students’ awareness and critical understanding of the difference between what you can mean and what you can do with digital tools and digital languages, be they verbal, visual, musical, etc.

The European project EU-MADE4LL: “European Multimodal and Digital Education for Language Learning” (2016-2019) I am involved in as coordinator is grounded in the assumption that teaching and learning digital literacies need a socio-semiotic and critical stance more than a technical and procedural approach. In our past experience, teaching English and digital communication to university students in Italy, UK and Denmark essentially meant more to instruct what do than to raise awareness in how to mean. Even though the use of digital texts – be they corporate webpages or videos, fanvids, blogs, video interviews, or video resume – is now common practice in foreign language learning, the critical and ideological implications still need to be charted. For example, assuming that English is used as an international tool of communication and as a lingua franca by non-native speakers, which is the English that needs to be taught and learnt? Who is the ideal assessor of students’ digital productions: the teacher, the prospective employer or the peer student, who may be a step forward, especially when it comes to evaluate geek culture that is progressively colonising multinational corporations?

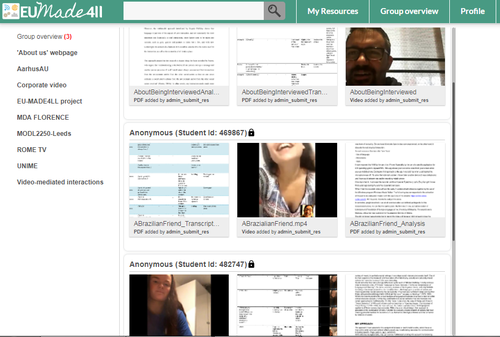

Digital skills seem to be very easily gauged and some commonly agreed criteria have been designed to help teachers, educators and practitioners in the field of digital literacies, such as The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens, published in 2017 by the Joint Research Centre (JRC) and including eight proficiency levels and examples of use. Within our EU-MADE4LL project, we are currently working on the design of the Common European Framework of Reference for Intercultural Digital Literacy(CFRIDiL), modelled on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFRL). CFRIDiL is based on data generated by over 200 students from five European universities, where they were taught how to produce and critically interpret and per-assess their peers’ digital texts, such as fanvids, video interviews, blogs, websites and corporate videos. We collected the students’ analyses and multimodal transcriptions of these digital texts in the platform shown below; all productions are the outcomes of our teaching and their learning on a common syllabus they had been taught in their home universities. The key component in our evaluation method was peer-assessment that involved all students. Evaluating a peer student’s digital production on a common set of criteria, including use of English as a lingua franca proved to be the most valuable exercise in intercultural awareness.

We assumed that being able to fulfil a task by using some digital skills, at a basic level, such as publishing a post on Facebook or commenting on a YouTube video, to more advanced tasks, such as professional video editing, cannot be equated with the socio-semiotic and critical understanding of what you are doing, your position (and bias) as a student (or researcher, or teacher, or professional).

We assumed that being able to fulfil a task by using some digital skills, at a basic level, such as publishing a post on Facebook or commenting on a YouTube video, to more advanced tasks, such as professional video editing, cannot be equated with the socio-semiotic and critical understanding of what you are doing, your position (and bias) as a student (or researcher, or teacher, or professional). These criteria can be applied to other digital scenarios, for example in the labour market, to question the underlying (c)overt ideologies that a simple digital text’s design entails, for example in deciding which language should be used (the so-called Standard English or English as a lingua franca? Or any other language? And for which audience?) or, on another level, reflecting on the language register to be adopted and for which overt or covert purpose (e.g. selling a product, such as a toy, a car, a university course, a health insurance?).

However, since the project’s early beginnings in a pre-pilot in 2010 in Messina (Italy), I have become more and more cautious about the ideological implications of any framework. If it is certainly useful to provide indications of levels of proficiency, be they in language or digital skills, aiming at standardisation, the danger of losing touch with intercultural awareness in communication is around the corner. Therefore educational efforts at global standardisation in teaching and learning need to be counterbalanced by intercultural awareness.

Peer assessment between students that come from different countries and different educational systems is a strategy to raise such awareness – and more so when face-to-face interactions are giving way to decontextualized and evanescent digital communication.

References

Baldry, A., Thibault, P. Multimodal Transcription and Text Analysis: A Multimedia Toolkit and Coursebook, London, Equinox, 2006

Web references

Project website: https://www.eumade4ll.eu/en/home-1/

Project platform: http://learnweb.l3s.uni-hannover.de/