Guest blog by Caroline Ardrey

In this guest blog, Caroline Ardrey, University of Birmingham, shares her approaches to sound within and between languages.

As Modern Linguists, many of us have the privilege of having a foot in various disciplinary camps. For some of us, our research interests tend towards history, looking at ways in which the societies and cultures of the past were mediated through language. For others, research in Modern Languages is highly topical, dealing with experiences of political regimes, border-crossing or exile, and examining ideas of identity. There are, of course, many, many more facets to Modern Languages research which, directly or indirectly impact upon our understanding of the world we live in, and pertain to one of the defining qualities of our species—the ability to communicate through speech and writing.

Often, when we think of archival research, and source-based criticism, using either digital or physical materials, most of us immediately imagine working in old-fashioned libraries, poring over traditional texts or visual media—books, journals, newspapers, letters, drawings or photographs. As we saw through the many fantastic presentations at the Language Acts digital workshop, the sources and archival materials which Modern Linguists collect to use in their research range from paintings to Whatsapp chats, from journals to blogs, and from digital editions to webdocs. Increasingly, many of us are drawing on new media and digital culture in our research, and / or using digital humanities methodologies to offer new approaches to studying traditional sources.

Using digital tools to study contemporary digital or non-standard media often means that we are building our research on shifting sands: we have to tackle different questions to those we’re used to approaching in traditional text-based scholarship, and we often need to develop new tools and methodologies in order to do this. Working with sound recordings is a prime example of the way in which new digital methodologies—still in their infancy—are being developed to study literary works in performance, and to analyse the cultural and linguistic impact of song. A key question for those of us working on these kinds of audio ‘texts’ within Modern Languages departments is: how do we share new approaches and good practice not only within languages but also between languages?

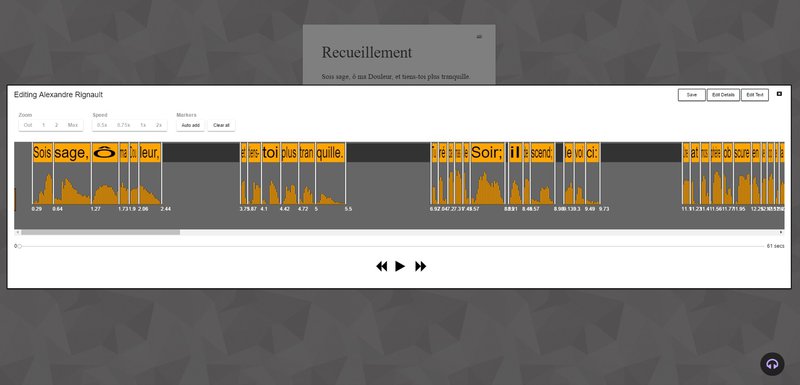

Digital tools lend themselves very well to examining digital audio sources, offering additional accuracy and detail to the highly subjective field of oral performance studies. Whether using readily available software such as Sonic Visualiser, Audacity and Max, or purpose-built tools, digital audio analysis techniques can be applied to the study of all kinds of digital sound sources, from telephone calls to pop songs, and from radio programs to film soundtracks. These tools might be used to compare the speech styles of television continuity announcers at a particular cultural moment, or to trace performance histories in spoken declamation of poetry, from the vinyl boom of the 1950s, to the YouTube age.

My own research is primarily concerned with the performance of poetry, in speech and in song. This field of study stands at the intersection between languages, performance studies and music technology, to name but a few fields. Annotating and analysing recordings of oral performances, using techniques which start from TEI-XML, is illuminating, revealing wide ranging interpretations of the same text, evident through accent, rhythm, musical settings and textual manipulations, such as altering words or structure in fusing words and music. These kinds of transformations of a text are relatively straightforward to pinpoint and evaluate when working with a single language, but what happens when we try to apply digital methodologies developed for working in one language to the study of another?

The question doesn’t only pertain to differences of language: it relates to dialectical features, and to differences in creative practice and cultural traditions. While, we might analyse the use of alexandrines, and the pronunciation of mute ‘e’ sounds in spoken declamation of French poetry, in German poetry, which hinges primarily on stress patterns, such considerations might be irrelevant. While we might find that some of the metrical concerns in the oral performance of Italian poetry are also relevant to those of us working with readings of Spanish verse, for others working in Russian or Cyrillic languages, the parameters by which we judge a text will be quite different.

As a discipline Digital Humanities often has to defend itself against accusations of ‘re-inventing the wheel’, and to make the case for the relevance of its contribution to humanities research (cf. Edwards, 2012; Posner, 2013; Kloser, 2016 to name but a few). While some might argue that DH often does involve developing new tools to tackle similar research questions, the frequent cycles of renewal and the tendency for self-evaluation in DH can be viewed as a strength, allowing new perspectives on well-studied topics, and facilitating cross-disciplinary insights, particularly as far as Modern Languages are concerned. A lack of parity between linguistic features and textual practices in different cultures means that some re-invention is both inevitable and beneficial. However, the divergence between languages, and between the various sub-disciplines in which Modern Linguists work invites diverse interdisciplinary collaboration. The fusion of literary and performance studies with DH sets the terrain for a very fertile crossover, further enhancing the polyvalence of each. The methodologies we develop as linguists and specialists in literature and performance studies, are further enhanced when we work together to promote such interactions, and to understand and celebrate those areas in which linguistic differences lead our methodological approaches to diverge into new and fruitful avenues.

References

Charlie Edwards, “The Digital Humanities and its Users”, Debates in the Digital Humanities (edited by Matthew K. Gold), Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), pp. 213 – 232.

David Kloster, “Networks”, CyberDH [blog], 11 October 2016 https://www.indiana.edu/~cyberdh/author/dkloster/

Miriam Posner, “No Half Measures: Overcoming Common Challenges to Doing Digital Humanities in the Library”, Journal of Library Administration, 53: 43-52 (2013) http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2013.756694